This post will be about the first 25 pages of the arrow lecture itself and will follow the order of sections contained in the book. My self-overvation is that I will be unable to stick to the order of topic of the lecture itself, as my understanding of the text is a result of connecting different points made by Dasgupta, und presenting my reading of the book, literally and metaphorically, is the whole point of this project.

Code can be found on here.

Demarking the subject

My understanding of section 1.1. is as an introduction into the subject via demarkation vis-a-vis already existing ones, outlined in the table below. I have also added categories from where I understand the topics to be originating from in order to fix and show my mental model of the topic we are beginning to talk about.

I found the sequencing of the introduction confusing as we start with the individual motives for having children which I understand to be broadly ethical and cultural and switch rapidly into a lengthy discussion of the economic intentions and consequences of decisions by parents concerning their intended and realised fertility. Following we switch back to a more rigid formulation of the ethical questions we started with. The (sneaky segwaying) addition of Question (iv)(p.6):

How should one value possible polulations so as to decide which would be best?

leads Dasgupta to Parfit stressing the difference between their opproaches. His main criticism consist of the denial of socio-ecological constrains in Parfits’ arguments, a criticism I find reasonable. I read Pasgupta as positioning himself in clear opposition to Parfit, but at this point of the book I would not agree to his understanding. Considering constraints is the definition of economics, regardless of the topic this consideration is applied on. If the optimal number of people in a society would not exceed existing socio-economical limits, we would never find out about them, and they would not be binding. Understanding socio-economic limits as normatively binding independent of the externalities for other present or future persons implied in their overuse seems to me a clear instance of the is-ought distinction. Of course Dasgupta would react to this critique by citing as the source of normativity the actual and potential well-being of present and future persons.. My main point here is that I do not think that Dasgupta works in the same field as Parfit, and I much rather read this book than one by Parfit.

This leads me to the following taxonomy of the topics discussed here:

I named the second column to demark the difference economics would typically be concerned with: micro and macro. I want to stress that this categorisation does not imply any kind of hierarchy - I do not think that practical philosophy is all we will ever have to say about ethics and that the idea of ethical expertise does not stand the empirical test, either by akrasia or worse, leaving me to the conclusion that a dialogue between disciplines and viewpoints concerning ethical considerations to be a wonderful and enriching thing to have.

Futher adding to my confusion was the fact that we get a short introduction into the global demographic transition with the first table strongly suggesting the concept of differing regimes between which populations in their dynamics switch, even mentioning the respective selection theory and regimes having differing evolutionary stable equilibria - I find interesting that this fact is mentioned in the footnote but the main text concerning externalities and the tragedy of the commons does not elude to the game theoretical dynamics governing those. Combining the topic of the book with the demographic transition, I just want to stress that the revealed preference of inhabitants of advanced economy is to have less children, leading an economist regarding the choice for or against children as a choice between different goods to classify them as an inferior good. Apart from the calculations, models and normative assessments regarding the optimal size of populations, the individuals actually making choices seem to have clear priorities.

Dasgupta then lays out the program for the rest of his lecture after his introductionary remarks:

Build a model

Feed data into the model

My understanding is that the following sections until the start of part one constitute in principle a kind of ontology and other considerations which the model will be based upon or trying to incorporate.

Utilitarian Ethics

I will first try to formalize how Sidgwick is discussed and then what modifications Dasgupta already establishes. I will also try to differentiate differing objects of analysis, namely individual I, actions a and societies S.

Supposed we wanted to model an individual life L the sum of events added chronologically:

Following utilitarianism the way to determine total individual utility U of a life would be by assigning a happiness value h to each event and summing up:

with h(n) having possible values positive to negative infinity (for simplicities sake).

Shifting the object of analysis to individual actions, we would then calculate similar to overall utility of a life:

with a, the first person to consider and b the total sum of people being affected by the given action. Notice how the meaning of the calculus changed without the equation at all. Furthermore we can use U^a to compare potential states of the world to each other as well - that is after all exactly what we do when considering the desirability of an action within a utilitarian framework.

Already we can see that selflessness is mandatory within utilitarianism, as there is no privilege given to the person supposed to do the action in U^a.

Ranking alternative states of the world between each other also becomes easy as we established a uniform currency in happiness into which we assume to subsume every relevant aspect of judgement, leading to a simple way of evaluating actions and states of world in which more utility is better and equal amount of utility denotes indifferent states between which no judgement can be reached upon. Let us assume together with Dasgupta that our criterion for happiness is sufficient complex to avoid all pitfalls for the arguments' sake. I do think that the addition of informed desires can do a lot of lifting by inserting a lot of enlightenment concepts concerning for example self-inflicted tutelage in combination with higher-order volition.

Similar to our simple summation operation computing the value of a single life, we can judge whole societies by summing the overall utility of all members:

Starting at a random person c living within the society and ending with last person d. Of course the same functionality regarding states of the world from U^a applies here as well: we now have a way of determining not only a positive society but also potential changes to it enabling us to do normative prescriptions in addition to descriptions of the world. Of course, we achieved all this by assuming away all problems of epistemics, perspective, individuality, legality and a dozen other things but we want to model with a certain goal in mind to get a better idea about some of our intuitions, and we will discuss ontology and methodology at a later point in the book where we can pick up what we left here. Besides the qualifications of informed desire and using well being instead of happiness I find the discussion about the necessity of consumption of goods and services to achieve a state of happiness noteable. I personally would be quicker to admit this as an epistemic problem we as human societies have not solved satisfyingly, but have no quarrel diagnosing empirically the consumption of goods and services as a necessary condition for happiness in a utilitarian sense for most people and activities in such a way that assuming the corner cases away seems reasonable. To me the epistemic lens of this is much more interesting than potential ethical dilemmas regarding this specific model. The epistemic considerations lead to lots of complicated normative questions of a totally different kind as Mazzucato pointed out.

To summarize, Dasgupta lays out his plans to modifiy what I laid out of Sidgwick here in the following ways:

Modifying desires into informed desires to avoid pleasure automata (already done here)

Shifting the unit of analysis from a temporal dimension to a material one (or simply adding it to the other) by introducing goods as a necessary condition of the fulfillment of informed desires (both done here on page 7-9)

Declaring his intention to at a later stage change the aggregation function for overall well-being by inserting a model of generations,

as well as a different understanding of the “neutral” life

Theses four changes to my understanding will lead to his theory of Generation-Relative Utilitarianism.

Ends and Means

This chapter deals with the second point of the list above - the material conditions within which well-being is to be realised and assessed. It starts by introducing in essence an ontology upon which the following modelling will be based. I love how the point of activity and services is stressed throughout, focussing on the dynamical nature of the object of economic measurement generally and the meaning of GDP specifically. I would like to point out that though GDP is mentioned, Dasgupta sets up the whole exercise as I understand it in opposition to conventional economics and/or econometrics, using the tools it itself uses to work on problems that will probably lead to different sociological, political and ethical positions.

Capital Goods

For my own understanding the first distinction to make is that between Economic Activity at a certain point or space in time t and that part of human activity that does not fall in that category, a distinction that Dasgupta in my reading of the text just assumes - if he does not, it is at least needed for me as a helpful frame around the modeling. As non-economic human activity is not concerned with life processes that are relevant for axiology, I find this reasonable.

Economic activity is then split up into services and assets which is derived from their relationship to time: Services being perishable in the sense that the act of consumption of a service through its temporality leaves other people at a later time unable to consume the same unit again. I find fascinating the use of metaphor describing the value of an asset as the (discounted) expected value computed as the services it will be able to perform in the future. Taken seriously, this would make goods ontologically dependend upon services which would be the fundamental category of economics shifted? The emphasis on dynamics is mentioned before and quite new to me. I find it pretty helpful, even if this is not a paradigm or intuition shared by many.

Services as an category seem to be assumed to be understood without further need of decomposition, but assets are further separated into the sum (S) of all types of capital and enabling assets. Here we see a rather stark contrast to conventional economic ontology, classifying financial means not as capital (which would be a lot of peoples intuitive example of capital, and all other forms of capital being ontologically dependend upon it or at least metaphorically derived from there), but as an enabling asset. I think we can see a lot of foreshadowing here how different the conclusions of the developed model may be from typical models that are to be contrasted here.

Following some possible types of capital categories are discussed and we arrived at three different forms: natural, permanent and human capital.

Dasguptas argument for limiting the categories of capital to those three as the ones that we are sufficiently able to price/measure is for the purpose of modeling sensible (even though this is a practical argument). I found Bourdieus’ differeing forms of capital extremely helpful as an epistemic tool understanding society, especially when combined with, paradoxically, Luhmann understanding different forms of capital simple as the corraly of different kinds of currencies one can spend in different systems and in part even convert into each other, but I would consider this a “soft” theory of which I would not be able to give an intuition how to build a model out of it. Dasguptas point here is that a lot of economic activities consist of converting at individually profitable rates different forms of capital into each other, most prominently natural into produced, and produced into human (at least how I picture it intuitively). Even if societal or (softer criterion) individual conversions may be profitable (we will get to well-being soon), it seems intuitive to assume differences between the types of capital. Natural capital may have regenerative aspects to it (gathering firewood out of a forest without cutting trees), enabling a potentially steady state of extraction. Produced capital seems to not regenerate and always degrade, if at different and even negligable rates (roman concrete). Human capital of course is the hope of decoupling, could be potentially infinite and enable non-zero-sum economics even in the field of usage or access in contrast to produced capital where the question of distribution of delivered services will always be at least implicit political.

I visualised the nesting of categories in order to get a better overview (Code available at the repository for this review:

Inclusive Wealth & social well-being

After discussing the means before, we now turn to the ends of it all: How should the extension of h in our starting point for utilitarianism be integrated into the model such that we can use happiness as a currency? (I repeated the formula from above)

The question comes up because what we absolutely do not want to do is simply rebuild a typical (macro-)economic model with money as the central accounting mechanism. To me the answer to this question seems to be given on page 15., with the answer being well-being and it being described as:

A person’s well-being is shaped by the extend to which her projects and purposes are realized. They in turn are rooted in her engagements, both with her own self and with others [..], which means account prices of goods and services are person-specific. It also means that the degree of fairness in the distribution of well-being influences accounting prices.

I would like to make several comments to that:

We can see here how in this model wants are theoretical unlimited, but means will always be - the typical problem of economics dressed (down) in utilitarians cloak.

There is (yet) no theoretical reason why more basic desires should be prioritised over more complex ones - like our current economies do, where rich people can price out poor people as a result of different means, unrelated to the urgency of their need.

There is now clearly a need for temporal discounting, which I will lay out below.

The constant stressing of the difference between “real economy”, how things are run at the moment and this model brings me to the merciless normative demands utilitarian poses to people. It is a really demanding normative theory!

Combining the third point with the point from the quote about person-specificity: Both the normative demands and the nuance are then just assumed away by modeling the economy with just one representative agent over an infinite time horizon.

My impression is that just establishing well-being as the truly relevant moral end to strive to is already revolutionary enough - never mind the inclusion of resource limits or moral considerations for future generations, at this point there is already such a chasm between what is described and implicitly prescribed that is difficult to bear on its own.

The role of temporal discounting:

Let’s imagine we wanted to implement a model how we know up until this point and do a genealogy to finetune if the model worked the way we think it should, and forgot temporal discounting. No primitive accumulation would happen and only rent extraction of those assets would be possible / permissable, as the undiscounted expected value of a natural asset over infinite generations would be infinte, and the undiscounted expected value of the resulting produced capital would necessarily be not infinte due to its main characteristic being degradation over time. No amount of faster population growth could justify the destruction of natural capital without temporal discounting. Amusingly enough, this would result in a behaviour that could be from the outside characterized as animistic, holding most of nature sacred in such a way that may feel like having a personal relationship with certain aspects of it. So we can see here that temporal discounting in effect enables the model to have something like a “developmental” stage of an economy where natural capital is unsustainably converted into other form of capital - with the implied hope that our children will be able to use those other forms of capital to get the whole system into a steady state or even make whole what was lost before.

At the same time, a more complex theory of natural capital would of course try to implement something like local or even global tipping points, with the collapse of the amazonas rainforest due to the collapse of its own climate feedback loop the most prominent example of a combination of both levels at the same time.

Inclusive Wealths’ radicalism

We call the social worth of the three classes of capital goods inclusive wealth [which] [..] includes human and natural capital

At this point my mapping is that within a given society inclusive wealth is counted by adding social worth of all capital goods up (ignoring markets here!), and that social worth does not only consist of the amount of self-realisation (see the longer quote above) of persons living right now, but also in some way the value of the self-realisation of persons not yet living.

That the social value of a produced capital may vary with its ownership or type of access to it (as in the piano having a higher value to someone actually being able to play it) ignores typical market-centered valuation and does not even try to talk about pareto-frontiers. Similarly the point about institutions and practices being a key determinate of the worth of capital within a society - both these points imply that a social planer could increase social welfare by a lot simply by changing the distribution of property and structures of states, social practices, mores, and much more. This is to me on the one hand empirically correct, and still such a bold normative position to take. Serious utilitarianism does not make prisoners!

At the same time the modeling does not talk about distribution, and I would argue that a lot of the defined relationship between social well-being and inclusive wealth rests on the fact that this claimed to be ceteris paribus true, with the c.p. doing the actualy heavy lifting. It also assumes away the (epistemic) compexity of distributional choices within a society: who gets to keep the piano? Being a perfect social planner is really hard, apparently.

How to use it

We did all this contrasting with accounting prices to get a different notion of investment is my impression, especially with the inclusion of natural capital. The strength seem to be that defining it is easy: Every decision made that increases inclusive wealth and consequently over time social well-being is a sound investment, and the opposite being described as a degradation of the capital stock of a society. I love how we now have a heuristic that is utterly familiar and alien at the same time, by using a concept already established and applying it to another topic - a move very similar to the discussion regarding utilitarianism above where the same definition could be used on different objects to solve similar yet different problems. I wrote about the complex trade-offs regarding social investment of societies above when talking about discounting and would like to continue here.

If we assume natural systems to be on the whole relf-regenerating, we have formally three types of capital with fundamental different relationships to time: Natural capital will (assuming harm done to nature by humanity before) increase with time, produced capital depreciates and human capital will change in relation to decisions by society, including those regarding overall fertility. If a society decides to grow while not living in a malthusian world, I would assume human capital to grow, at equilibrium replacement human capital would behave similar to the amount of investment made into it in relation to the generation before, and with a declining population the investment would have to overpower the fact that the number of “goods” into which human capital is accumulated is shrinking overall - literally a basis effect.

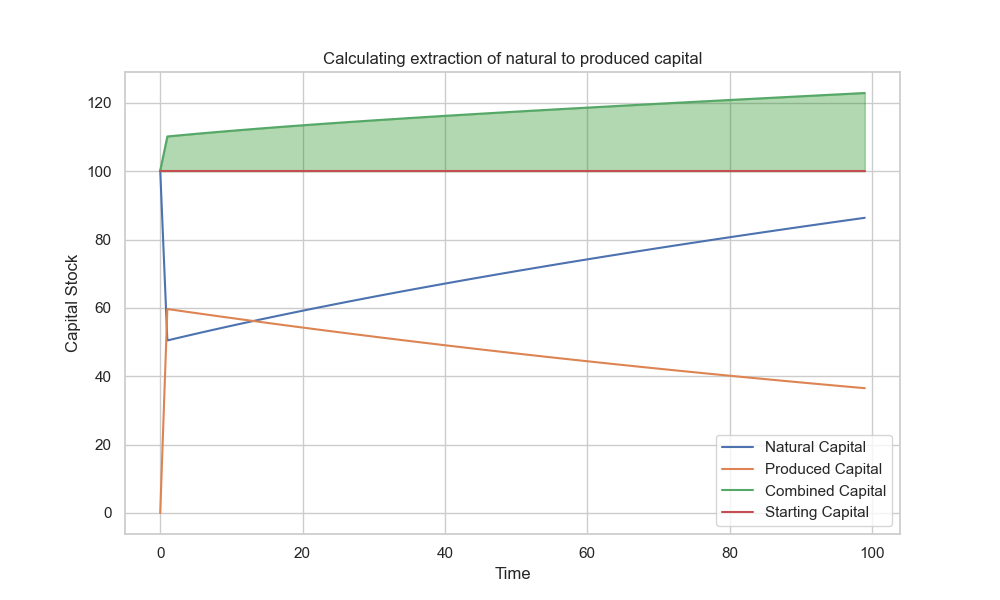

Scenario 1: Modeling one-time conversion

Regarding the idea of investment decisions it is already said that some amount of produced capital would be needed to form and maintain human capital, but that relationship seems to be quite opaque. The conversion of natural into produced capital seems rather clear cut that I felt invited to do some simple calculations and plot them to get a feel for the dynamics at play.

Let us assume first that we have a given stock of natural capital with a value of 100, and one generation extracts a certain amount of it and converts it at a certain rate into produced capital. That produced capital then depreciates according to a constant and the natural capital regenerates asymptotically to the original value.

Lets start with a conversion rate of 1.2, a flat extraction amount of 50, a replenishing basis of 25 (adding to the natural capital stock the base at t times the rate divided by the base to the power of 2), a depreciation rate of 0.5%, over a time horizon of 100.

While this is a “happy story” in the sense that overall capital accumulates, it is probably not a likely story due to intertemporal distributional issues: Generation 2 got the biggest jump in well being, and everyone else is facing a depreciating stock of produced capital and has a regenerating natural capital that increases overall capital. Just imagine the difference in values compared to our current ones needed to make this a politically stable arrangement….

Lets be techno-optimists and assume rapidly better technology at the point of extraction with a conversion rate of 2 and a depreciation rate one fifth of the first simulation!

Natural capital replenishes the same as before, but the growth in overall capital is much more. Notice how the better extraction rate makes the intertemporal distributional conflict more pronounced even against the backdrop of intense imbalance of improvements: We increased the extraction rate by 2/3, but divided the depreciation by a factor of 5! (which if one timestep is supposed to be a generation would be crazy value to start with).

Lets be a little more pessimistic about the gnawing of time and half the regeneration basis of natural capital while doubling depreciation of produced capital to 1%, it really starts to bite:

This intertemporal distributional conflict is no longer about who gets to grow how much but who takes the hit for others to grow, pretty ugly. As the code is available to play with, getting a feel for this scenario is available to all.

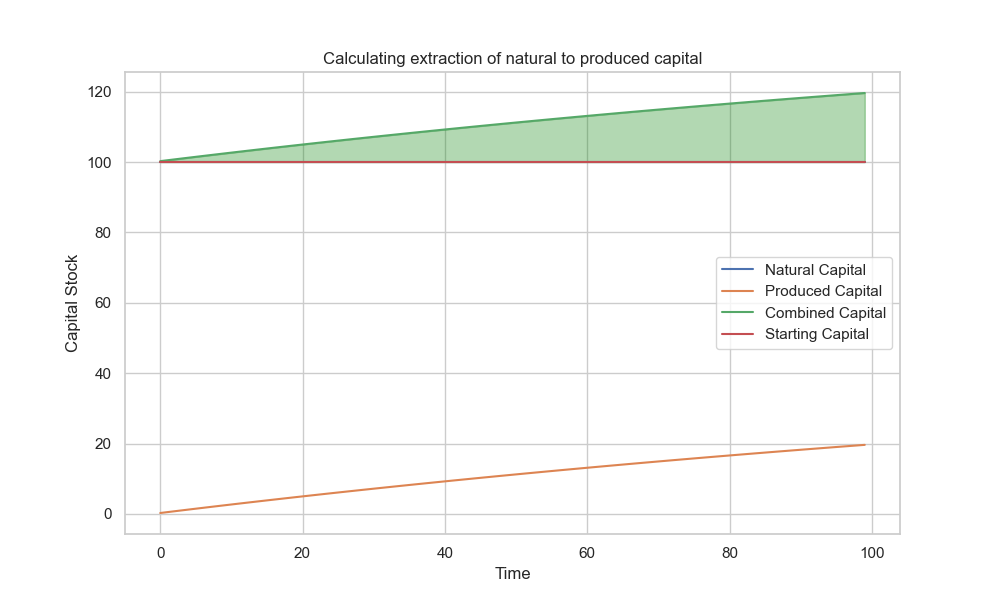

Scenario 2: Modeling constant extraction rates

Let us assume the generations would like to avoid intertemporal distributional conflicts by extracting constant amounts of natural capital and converting it into produced capital every step of the simulation and see where this leads us. We start again with a stock of 100, a conversion rate of 1.2, a replenishment basis of 25 and a depreciation basis of 0.5% and extract the same amount of natural capital each time:

We see here how the generations avoid conflict with each other by:

Exploiting the externalities - the stock of natural capital will be depleted some day, and we have good reason to assume that degredation is non-linear because of biological system effects, and the same is probably true for the impacts on human well being.

Accepting massive opportunity costs in the form of binding their own growth trajectory to that of the biosphere. Consider that scenarios of scenario 1 are theoretically all the time possible for each generation as an alternative. Here as well we can say that for this to be sustainable, the generations would need a radically different kind of morality that the one we exhibit at the moment.

If we halve the extraction rate to 0.25%, degredation of natural capital can be avoided completly with a slow build up of produced capital stock, the generations even gain a little overall compared to the basis scenario 2:

This seems to be strictly dominating the first scenario of constant extraction in that it avoids the intertemporal distributional conflict while being sustainable regarding natural capital, although the second point still stands here.

Next, let us assume that the extraction rate is double that of the base scenario to get an idea about the amount of discipline needed to maintain the natural capital - just assume our generations do exhibit the shifting baseline effect. An extraction rate of 1% per step yields:

This.. does look like biosphere collapse while everyone is still feeling fine as progress is still happening - produced capital is growing after all, right?

What if we run the techno-optimist scenario with a conversion rate of 2 and a depreciation rate of 0.1%?

Obviously the biosphere degrades the same as in the base scenario case 2 (each generation extracts the same in both scenarios) but we get more growth - alas, the dimensions are still quite sobering, about 7 percentage points more from the starting point, but with fundamentally better technology, over a time horizon of 100 periods.

Turning to the last variable left unchanged, if we double the regeneration basis of natural capital for both base scenarios, we get for the one time extraction:

There could obviously some kind of optimization be run on the consumption model where it is done several times in order to exploit the faster regeneration at lower levels of natural capital - but the point of this exercise was to get some intuitions about the relationship between these two types of capital.

The same goes for constant extraction, where we could adjust the extraction rate proportionally to the regeneration base of natural capital:

What this simple modeling shows to me is the radicalism of the introduction of natural capital into the summation of social well-being. Accepting the systemic confines of nature as an equal input into our growth trajectories introduces really biting trade-offs in multiple dimensions. I do find the taxonomy of capital goods pretty convincing and am also not a delusional techno-optimist believing in unbound promethean potential of human ingenuitiy. As such, natural capital seems to be the ground base for all other forms of capital either directly of via transmission for produced to human capital. I would also like to stress at this point that we have not even talked about population growth and fertility decisions yet. I suspect once those enter the picture, things will get much more complicated than that.

I mentioned several times how there would have to be radically different morality in order to keep certain extraction strategies stable across time and would like to stress here that my line of thinking there was to assume lived ethical practice as a solution to intertemporal distributional issues “What kind of generations/societies would be needed to keep this behaviour stable?” as a causal story. The rationalistic wording for such a causal story would be “What kind of incentives would each generation need to keep the exhibited behaviour evolutionary stable within their societies?”.

I have on the one hand quite materialistic beliefs regarding the formation of moral judgements of persons and huge respect for biases and desireability of feeling self-affirmation and a positive self-image. At the same time, I do think moral progress is possible because empirically it happened and do believe that one of mankinds most astounding and redeeming feature to be imagination and a strive to do and be better - leading me to believe in the possibility of quite a different morality than we currently observe, with all the great and horrible implications that entails. I am sure we will return to our musings here at a later time.

Placing a value on opportunity sets

This to me is the hardest section to interact with from an emotionally productive stance. I have no horse in this race, and find the argumentation whose model is the better universal model of “Life, the Universe and Everything” overall pretty pointless. What’s more, I feel unable to learn something new from this pedantic point of view in a pretty specialised debate about modeling assumptions and if one model is theoretically subsumable into another. To me, the whole point of models is them being an epistemic tool, and this has no relation to their ontological relationship to each other. If capability theory enabled policy maker on the ground by providing a more intuitive framework and epistemic shortcuts to estimations of total utility even approximately correct, why would any utilitarian object? That is of course my inner pragmatist speaking - if that was not my emotional stance towards these discussions, I would probably be having them more, even enjoying them.

In particular the mentioned proof that foregoing choosing between different capability sets as akin to option buying feels rather mood. Of course that is a way to understanding it but a way of understanding every decision situation in which waiting for further information at a clear or opaque price is a possibility - so the point of this “reduction” is another than to clarify assumptions, it is to implicitly declare superiority of one model over another. If every model is wrong but some are useful, which I believe (of course I have to have a Meta-Theory for that, but that theory is decidedly not utilitarianism as it is not concerned with questions concerning such topics), I would concern this to be an invalid move in the language game, that being models and positions criticising each other in order to improve each other and themselves.

I furthermore do share some intuitions regarding Qualia and think some parts of the decision made by human being to be a plumber or a teacher really hard to communicate satisfyingly as a result of the fact that the feeling of being a body within a certain society fulfilling certain social roles to not be in toto shareable, even if understandable. If we will never be able to understand how it feels to be a bat, the same has to hold true with place and roles in society. Trying to subsume all this into pure numbers as utilitarianism does seems to me to be an epistemic shortcut valid in the face of the difficulty, but no reason for triumphalist declarations, quite the contrary: I would behoove us to remind ourselves of the limits we encounter everyday and practice (epistemic, ontological) humility in the face of them.

Wrapping up

My initial goal was to write about the next 11 pages as well, but this post is already way too long. It feels great to give a text this amount of care and thought. The topics discussed, especially reflecting upon the normative orders and their relation to types of (primitive) produced capital accumulation resonated with me and reminded me of le Guins wonderful translation of the Tao te Ching, poem 29, Not doing:

" Those who think to win the world by doing something to it, I see them come to grief. For the world is a sacred object. Nothing is to be done to it. To do anything to it is to damage it. To seize it is to lose it. [..] "

This feels like a starting point pondering what societies the modeling this book proposes actually wants us to become. I think we may become better people as a result, but that is of course a value judgement on my part.